Dr. Burak Hacıhanefioğlu

polycysticovary.net internet sitesinde yer alan tıp içerikli yazı ve videoların tümü Kadın Hastalıkları ve Doğum Uzmanı Dr. Burak Hacıhanefioğlu tarafından hazırlanmış olup, telif hakları yasal koruma altına alınmıştır. İzinsiz kaynak gösterilerek dahi başka bir yerde yayınlanamaz.

Human Papilloma Virüsü (HPV) rahim ağzı kanserine (cervical cancer) neden olmaktadır(97,129). Son yıllarda HPV’ ye karşı korunmak amacıyla bazı aşılar üretilmiştir(92,95,124). HPV aşıları bazı ülkelerde yaygın olarak önerilmekte olmasına rağmen rahim ağzı kanserinin önlenmesi amacıyla kullanılabilecek tek yöntem aşı değildir(45,104). HPV aşısı yapılan bir kadının rahim ağzı kanseri olma ihtimali, belirli aralıklarla rahim ağzından akıntı örneği alınarak yapılan HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testi ile takip edilen bir kadından daha az değildir(21,31,32,45,83,92,93,95,100,101,104,108,115,121). Kongo gibi afrika ülkelerinde (Sub-Saharan Africa) ve Fuji gibi pasifik okyanusundaki adalarda rahim ağzı kanseri dünya ortalamasından çok daha fazla görülmektedir(28,29,109,129). Bu ülkelerde yaşayan kadınlara doktora ulaşma, HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testi yaptırma şansları oldukça düşük olduğu için toplu olarak (mass vaccination) HPV aşısı yapılması doğru olabilir(108,109,129). Fakat, kadınların doktora ulaşma, HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testi yaptırma şanslarının yüksek olduğu ülkelerde HPV aşısının kişinin tercihine ve isteğine bağlı olarak (voluntary vaccination) yapılması daha doğru bir yöntemdir(104,109). Rahim ağzı kanserini engellediği kesinleşmemiş olmasına rağmen, aşı olmayan kişinin rahim ağzı kanseri olacağı ve de aşı olmak istemeyen bir kişinin aşıdan başka çaresi yokmuş gibi gösterilmesi doğru değildir. HPV aşısı üreten ilaç firmalarının maddi desteğiyle yapılan bazı çalışmalarda HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testinin başarısı düşük bulunmakta ve hatta bu testlerin yapılmasına gerek olmadığı bile söylenmektedir(101,110). Halbuki, aşı olmayan bir kişinin, aşının tahmin edilen koruyuculuğundan daha fazla etkili olduğu yıllar önce gösterilmiş yöntemlerle (HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testi) korunması mümkündür.(21,31,32,55,77,80,81,83,85,87,88,90,93,94,95,97,100,101,104,110,115,120,121).

HPV’ nin 200′ den fazla çeşidi (genotypes) vardır(105). HPV nin genetik yapısında oluşan değişiklikler (mutasyonlar) her geçen gün yeni çeşitlerin ortaya çıkmasına neden olmaktadır(105,123,125). Bunlardan şimdilik yaklaşık 20 tanesinin rahim ağzı kanserine neden olduğu bilinmektedir(97,105). HPV aşısı ise rahim ağzı kanserine neden olan bu 20 HPV çeşidinden sadece bir kısmına etki etmektedir(11,15,97). HPV’ ye bağlı rahim ağzı kanserinin ortaya çıkması 25 ile 40 yıl kadar uzun bir süreyi bulabilmektedir(131). HPV aşısı kullanılmaya başlandığından beri yaklaşık 10-12 yıl bu kadar bir süre geçmiştir. Bu nedenle aşının rahim ağzı kanserine karşı koruyuculuğu da henüz bilinmemektedir.

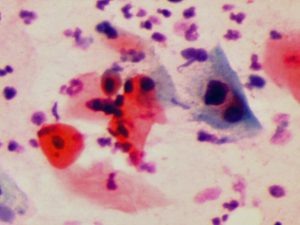

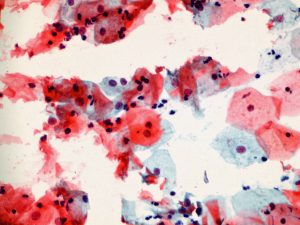

HPV aşısı rahim ağzı kanseri yapan HPV çeşitlerinin sadece bir kısmına karşı etkilidir(97). HPV aşısı HPV’ nin rahim ağzı hücrelerine yapışma (capsid) yerinde bulunan protein (L1) için antikor oluşturmaktadır(122). Rahim ağzı kanseri yapan HPV çeşitlerinde (genotypes) oluşan genetik mutasyonlar (L1 protein variants) aşının etkinliğini azaltmaktadır(123,125,126,127). HPV aşısı yapıldıktan sonra aşının koruyuculuğu (seropositivity) takip eden yıllarda giderek azalmaktadır(111,113,117,118,119). HPV enfeksiyonu (positive) olan bir kişiye HPV aşısı yapıldığı zaman aşının rahim ağzı kanserini önleyici bir etkisi yoktur(106,107). Bu nedenlerle HPV aşısı yaptıran kişinin de yaptırmayanlar gibi aşı yapıldıktan sonra HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testi ile aynı şekilde takip edilmesi gerekmektedir(100,112,114,116,118). Rahim ağzı kanseri olan kadınların büyük çoğunluğunda HPV çeşitlerinden biri veya bir kaçı saptanmasına rağmen, bir kısmında ise HPV tespit edilememektedir(128,129,130). Demek ki aşının tahmin edilen koruyuculuğunun kapsamadığı rahim ağzı kanserleri de görülmektedir(128,129,130). Bu nedenle HPV aşısı yaptırdıktan sonra aşının koruyuculuğuna güvenerek takibi bırakıp, pap smear testi ve HPV testi yaptırmayı ihmal eden kişilerde tam tersine rahim ağzı kanseri riski artabilir. Pap smear testi ve HPV DNA testi için muayene sırasında rahim ağzından, rahim ağzı kanserinin en çok görüldüğü bölgeden (transformation zone) çubuk şeklinde, ince bir fırça yardımıyla akıntı örneği alınır(65,70,71). Bu akıntı örneğinde görülen hücrelerde HPV DNA’ sının varlığını tespit etmek için HPV DNA PCR testi yapılır, pap smear testinde de akıntı örneğindeki rahim ağzı hücreleri mikroskop ile incelenerek HPV enfeksiyonunun neden olduğu değişiklikler görülür(41,51,54,57,58,59,65,70,71,75,77,86,91).

HPV aşısının kalıcı hasar bırakan ve ölümle sonuçlanan yan etkileri vardır(7,73,78,89). HPV aşısında bulunan bazı maddeler (antijen) beyinde bulunan sinir hücrelerini taklit etmektedir (cross-reactivity)(4,8,89). HPV aşısının bağışıklık (immün) sistemini uyarması sonucunda HPV aşısına karşı oluşan antikorlar görme sinirine (neuromyelitis optica) ve beyin hücrelerine (acute disseminated encephalomyelitis) zarar verebilmektedir(3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,62,73,89). HPV aşısı ailesel (genetik) eğilimi olan kadınlarda multiple sclerosis (MS) gibi bağışıklık sistemi (otoimmün) hastalıklarının ortaya çıkmasına neden olmaktadır(96). Japonya ve bazı Avrupa ülkelerinde yan etkileri nedeniyle HPV aşısı yasaklanmıştır(1,2,44,46,48,66,74).

HPV enfeksiyonu genellikle akıntı, kanama ve ağrı gibi şikayetler yapmamaktadır. Gözle görülemeyen, ancak mikroskop ile görülebilen hücre içinde bazı değişikliklere (Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) (SIL) neden olmaktadır(35,36,41,43,49,51,54). Bu hücresel değişiklikler ancak pap smear testi ile görülebilmektedir. HPV DNA testinde HPV enfeksiyonu tespit edilenlerin (pozitif) bir kısmında ise erken teşhis nedeniyle pap smear testinde henüz hücreye zarar verecek kadar süre geçmediği için hücresel değişiklik (SIL) görülmemektedir(12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,22,24,34,40,82,102,132). HPV DNA testi ve Pap smear testi birlikte yapıldığında bir kişide HPV enfeksiyonu olduğu halde bu testlerin yanlışlıkla yok deme ihtimali de, bir kişide HPV enfeksiyonu olmadığı halde yanlışlıkla var deme ihtimali de oldukça düşüktür(53,55,57,59,63,80,81,86,90,93,99,101,103,104).

Rahim ağzında görülen HPV enfeksiyonlarının büyük çoğunluğu (%90) normal bağışıklığa sahip olan kişilerde yaklaşık 1 yıl içinde, daha küçük bir kısmında da 2 yıl içinde kendiliğinden vücuttan temizlenmektedir (clearance)(23,24,25,26,27,30,33,37,39,42,43,47,56,60,64,69,76,79,84,98). Rahim ağzında yaptıkları hücresel değişikliklerin (SIL) büyük bir kısmı da (%90) 2 yıla kadar iyileşmektedir(23,24,25,26,27,30,36,38,50,52,56,60,61,67,68,69). Vücuttan temizlenmeyenlerin (persistence) büyük çoğunluğunu rahim ağzı kanserine neden olan HPV çeşitleri oluşturmaktadır(25,27,37,38,84). Rahim ağzında ortaya çıkan ileri derecede hücresel değişikliklere (Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia) (CIN+2) genellikle 3 yıl içinde vücuttan temizlenmeyen HPV çeşitleri neden olmaktadir(36,37,38,39,50,52,69,72,75,76,79,98). Rahim ağzı kanserlerinin büyük bir kısmına 2 yıl içinde vücuttan temizlenmeyen HPV-16 ve HPV-18 çeşitleri neden olmaktadır(27,30,60,98). Demek ki burada doğru olan 100 kişiden 90’ına kendiliğinden iyileşeceğini bile bile gereksiz yere ciddi yan etkileri olabilen bir aşının yapılması değil, rahim ağzı kanseri riski taşıyan kişinin tespit edilerek onun HPV DNA testi ve pap smear testi ile takibinin ve tedavisinin yapılmasıdır(75,80,81,83,93,97,99). Rahim ağzı kanseri ve ona bağlı gelişen ölümler çoğunlukla Pap smear testi ve HPV DNA testi yaptırmayanlarda görülmektedir(77,83,87,94,121).

∗Cinsel olarak aktif hayata başladıktan sonra belirli aralıklarla yaptırılan HPV DNA testi ve Pap smear testi ile HPV’nin neden olduğu ileride rahim ağzı kanserine dönüşebilecek hücresel değişiklikler erken dönemde kişi rahim ağzı kanseri olmadan teşhiş ve tedavi edilebilmektedir.

∗Belirli aralıklarla HPV DNA testi ve Pap smear testi yaptıran bir kişinin rahim ağzı kanseri olma ihtimali, rahim ağzı kanseri aşısı yaptıran bir kişiden daha düşüktür.

∗Herhangi bir yan etkisi olmayan HPV DNA testi ve Pap smear testi ile takibi yapılan bir kişinin kalıcı hasar ve ölüme neden olabilen yan etkilere sahip hpv aşısını yaptırmasına gerek yoktur.

Polikistik over sendromu olan kadınların yaklaşık yarısında çeşitli derecelerde insülin direnci görülmektedir. Polikistik Over Sendromu’ nda insülin direnci veya şeker hastalığı olan kadınlarda genital bölgede (Vajina, Vulva) tekrarlayan mantar enfeksiyonları daha sık görülmektedir.

∗İnsülin direncinin tedavi edilmesine bağlı olarak mantar enfeksiyonuna zemin hazırlayan ortam ortadan kalkmaktadır. Kötü hijyenik ortam ve ıslaklık (nem) mantar üremesini arttırmaktadır. Kötü hijyenik şartlar düzeltildikten (günlük ped kullanımının bırakılması gibi) ve kuru ortam sağlandıktan sonra insülin direnci tedavisi ve antibiyotik tedavisi birlikte uygulandığında mantar enfeksiyonu tedavi edilebilmektedir.

Kaynaklar

1-Who Profits From Uncritical Acceptance of Biased Estimates of Vaccine Efficacy and Safety? Tomljenovic, Shaw CA. Am J Public Health. 2012 September; 102(9): e13–e14. 2-Lessons learnt in Japan from adverse reactions to the hpv vaccine: a medical ethics perspective. Beppu H, Minguchi M, Uchide K, Kumamoto K, Sekiguchi M, Yaju Y. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics. Vol II No 2 April-June 2017. 3-Demyelinating disease and polyvalent human papilloma virus vaccination. Chang J, Campagnolo D, Vollmer TL, Bomprezzi R. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1296-1298. 4-Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following vaccination against human papilloma virus. Wildemann B, Jarius S, Hartmann M, Regula JU, Hametner C. Neurology. 2009;72(24):2132-2133. 5-Neuromyelitis optica following human papillomavirus vaccination. Menge T, Cree B, Saleh A, et al. Neurology. 2012;79(3):285-287. 6-CNS demyelination and quadrivalent HPV vaccination. Sutton I, Lahoria R, Tan I, Clouston P, Barnett M. Mult Scler. 2009;15(1):116-119. 7-The spectrum of postvaccination inflammatory CNS demyelinating syndromes. Karussis D, Petrou P. Autoimmun Rev. 2014 Mar;13(3):215-24. 8-Vaccination and autoimmune diseases: is prevention of adverse health effects on the horizon? Maria Vadalà, Dimitri Poddighe, Carmen Laurino, Beniamino Palmieri. EPMA J. 2017 Jul 20;8(3):295-311. 9-Simultaneous Bilateral Optic Neuritis Following Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in a Young Child. Ngu Dau Bing Michael, Tengku Norina Tuan Jaffar, Adil Hussein, Wan-Hazabbah Wan Hitam. Cureus. 2018 Sep 24;10(9):e3352. 10-Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine and autoimmune adverse events: a case-control assessment of the vaccine adverse event reporting system (VAERS) database.

17-Prevalence of Human Papillomavirus Genotypes and Abnormal Pap Smears Among Women in the Military Health System. J Community Health. 2018 Jun;43(3):441-447. 18-Human papillomavirus genotypes distribution by cervical cytologic status among women attending the General Hospital of Loandjili, Pointe-Noire, Southwest Congo (Brazzaville). Affiliati. J Med Virol. 2015 Oct;87(10):1769-76.

19-The relationship of human papillomavirus (HPV) detection to pap smear classification of cervical-scraped cells in asymptomatic women in northeast Thailand. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2001 Jun;27(3):117-24.

20-Frequency of human papillomavirus infection and genotype distribution among women with known cytological diagnosis in a Southern Italian region. J Prev Med Hyg. 2010 Dec;51(4):139-45. 21-Primary HPV testing versus cytology-based cervical screening in women in Australia vaccinated for HPV and unvaccinated: effectiveness and economic assessment for the National Cervical Screening Program. Lancet Public Health. 2017 Feb;2(2):e96-e107. 22-The prevalence and genotype distribution of human papillomaviruses among women in Taizhou, China. . 2019 Sep;98(39):e17293.23-Management of adolescents who have abnormal cytology and histology. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008 Dec;35(4):633-43; x.

24-Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection among Daqing City women in China with normal cytology: a pilot prospective study. . 2017 Aug 11;8(46):81455-81461.25-Minor Cytological Abnormalities and up to 7-Year Risk for Subsequent High-Grade Lesions by HPV Type. . 2015 Jun 17;10(6):e0127444.

26-Adolescent cervical dysplasia: histologic evaluation, treatment, and outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Aug;197(2):141.e1-6. 27-Type-specific prevalence and persistence of human papillomavirus in women in the United States who are referred for typing as a component of cervical cancer screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Mar;200(3):245.e1-7.28-Human papillomavirus genotypes distribution by cervical cytologic status among women attending the General Hospital of Loandjili, Pointe-Noire, Southwest Congo (Brazzaville). J Med Virol. 2015 Oct;87(10):1769-76.

29-Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. 30-Determinants of clearance of human papillomavirus infections in Colombian women with normal cytology: a population-based, 5-year follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 Sep 1;158(5):486-94. 31-HPV testing as a screen for cervical cancer. BMJ. 2015 Jun 30;350:h2372.32-American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002 Nov-Dec;52(6):342-62.

33-Factors associated with type-specific persistence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection: A population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2016 Jan 15;138(2):361-8. 34-Incidence, duration, and determinants of cervical human papillomavirus infection in a cohort of Colombian women with normal cytological results. J Infect Dis. 2004 Dec 15;190(12):2077-87. 35-A longitudinal study of genital human papillomavirus infection in a cohort of closely followed adolescent women. J Infect Dis. 2005 Jan 15;191(2):182-92. 36-Development and duration of human papillomavirus lesions, after initial infection. J Infect Dis. 2005 Mar 1;191(5):731-8. 37-Type-specific duration of human papillomavirus infection: implications for human papillomavirus screening and vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2008 May 15;197(10):1436-47. 38-Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Apr 2;100(7):513-7. 39-The natural history of human papillomavirus infection as measured by repeated DNA testing in adolescent and young women. J Pediatr. 1998 Feb;132(2):277-84. 40-Risks for incident human papillomavirus infection and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion development in young females. JAMA. 2001 Jun 20;285(23):2995-3002. 41-The 2001 Bethesda System: terminology for reporting results of cervical cytology. JAMA. 2002 Apr 24;287(16):2114-9. 42-Chapter 5: Viral and host factors in human papillomavirus persistence and progression. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;(31):35-40. 43-Regression of low-grade squamous intra-epithelial lesions in young women. Lancet. 2004 Nov 6-12;364(9446):1678-83. 44-HPV vaccination crisis in Japan. Lancet. 2015 Jun 27;385(9987):2571. 45-Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019 Aug 10;394(10197):497-509. 46-Outcomes for girls without HPV vaccination in Japan. Lancet Oncol. 2016 Jul;17(7):868-869. 47-Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1998 Feb 12;338(7):423-8. 48-No association between HPV vaccine and reported post-vaccination symptoms in Japanese young women: Results of the Nagoya study. Papillomavirus Res. 2018 Jun;5:96-103. 49-A study of 10,296 pediatric and adolescent Papanicolaou smear diagnoses in northern New England. Pediatrics. 1999 Mar;103(3):539-45. 50-Human papillomavirus persistence in young unscreened women, a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27937. 51-Endocervical and metaplastic cells: comparison of endocervical and metaplastic cell number in Papanicolaou smears with and without squamous intraepithelial lesion. . Mar-Apr 2006;50(2):178-80. 52-Type specific persistence of high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) as indicator of high grade cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions in young women: population based prospective follow up study. BMJ. 2002 Sep 14;325(7364):572. 53-Benefits and harms of cervical screening from age 20 years compared with screening from age 25 years. Br J Cancer. 2014 Apr 2;110(7):1841-6. 54-The significance of squamous metaplasia in the development of low grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in young women. Cancer. 1999 Mar 1;85(5):1139-44. 55-Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Aug 10;8(8):CD008587. 56-Cervical cytology testing in teens. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;17(5):471-5. 57-Pap smear adequacy: Is our understanding satisfactory…or limited? Diagn Cytopathol. 2001 Feb;24(2):79-81. 58-Endocervical component in conventional cervical smears: influence on detection of squamous cytologic abnormalities. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007 Apr;35(4):209-12. 59-The significance of endocervical cells and metaplastic squamous cells in liquid-based cervical cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009 Apr;37(4):241-3. 60-Prospective evaluation of longitudinal changes in human papillomavirus genotype and phylogenetic clade associated with cervical disease progression. Gynecol Oncol. 2011 Feb;120(2):284-90. 61-Natural history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a critical review. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993 Apr;12(2):186-92.62-A 16-year-old girl with bilateral visual loss and left hemiparesis following an immunization against human papilloma virus. J Child Neurol. 2010 Mar;25(3):321-7.

63-False negative rate in cervical cytology. J Clin Pathol. 1987 Apr;40(4):438-42. 64-Human papillomavirus infection is transient in young women: a population-based cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1995 Apr;171(4):1026-30.65-Efficacy of cervical-smear collection devices: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 1999 Nov 20;354(9192):1763-70.

66-HPV vaccination programme in Japan. Lancet. 2013 Aug 31;382(9894):768.67-Behavior of mild cervical dysplasia during long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1986 May;67(5):665-9.

68-Biologic course of cervical human papillomavirus infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Feb;69(2):160-2.

69-Natural history of cervical human papillomavirus lesions does not substantiate the biologic relevance of the Bethesda System. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 May;79(5 ( Pt 1)):675-82.

70-A comparison of the three most common Papanicolaou smear collection techniques. Obstet Gynecol. 1994 Aug;84(2):168-73.

71-Liquid-based Papanicolaou smears without a transformation zone component: should clinicians worry? Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;99(6):1053-9.72-Cervical dysplasia in adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Jul;106(1):115-20.

73-Monitoring the safety of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from the Vaccine Safety Datalink. Vaccine. 2011 Oct 26;29(46):8279-84.

74-Progress and challenges for the Japanese immunization program: Beyond the “vaccine gap”. Vaccine. 2018 Jul 16;36(30):4582-4588.

75-Risk of invasive cervical cancer in relation to management of abnormal Pap smear results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;201(2):188.e1-7.

76-Patterns of persistent genital human papillomavirus infection among women worldwide: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2013 Sep 15;133(6):1271-85.

77-Accuracy of the Papanicolaou test in screening for and follow-up of cervical cytologic abnormalities: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000 May 16;132(10):810-9.

78-Quadrivalent HPV vaccination reactions–more hype than harm. Aust Fam Physician. 2009 Mar;38(3):139-42.

79-The natural history of human papillomavirus infection. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018 Feb;47:2-13.

80-Long term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Oct 13;337:a1754.

81-Long term duration of protective effect for HPV negative women: follow-up of primary HPV screening randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014 Jan 16;348:g130.

82-Prevalence and determinants of HPV infection among Colombian women with normal cytology. Br J Cancer. 2002 Jul 29;87(3):324-33.

83-Impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality: estimation using stage-specific results from a nested case-control study. Br J Cancer. 2016 Oct 25;115(9):1140-1146.

84-Type-specific persistence of high-risk human papillomavirus infections in the New Independent States of the former Soviet Union Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007 Jan;16(1):17-22.

85-Distribution of 37 mucosotropic HPV types in women with cytologically normal cervical smears: the age-related patterns for high-risk and low-risk types. Int J Cancer. 2000 Jul 15;87(2):221-7.

86-HPV for cervical cancer screening (HPV FOCAL): Complete Round 1 results of a randomized trial comparing HPV-based primary screening to liquid-based cytology for cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2017 Jan 15;140(2):440-448

87-The association between cervical cancer screening and mortality from cervical cancer: a population based case-control study. Gynecol Oncol. 2014 May;133(2):167-71.

88-Low false-negative rate of PCR analysis for detecting human papillomavirus-related cervical lesions. J Clin Microbiol. 1998 Sep;36(9):2708-13.

89-Post-vaccination encephalomyelitis: literature review and illustrative case. J Clin Neurosci. 2008 Dec;15(12):1315-22.

90-Clinical human papillomavirus detection forecasts cervical cancer risk in women over 18 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Sep 1;30(25):3044-50.

91-Multiple high risk HPV infections are common in cervical neoplasia and young women in a cervical screening population. J Clin Pathol. 2004 Jan;57(1):68-72.

92-Reduction in human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence among young women following HPV vaccine introduction in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 2003-2010. J Infect Dis. 2013 Aug 1;208(3):385-93. 93-Five-year risks of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer among women with HPV-positive and HPV-negative high-grade Pap results. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013 Apr;17(5 Suppl 1):S50-5. 94-Screening-preventable cervical cancer risks: evidence from a nationwide audit in Sweden. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 May 7;100(9):622-9. 95-US assessment of HPV types in cancers: implications for current and 9-valent HPV vaccines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Apr 29;107(6):djv086. 96-Vaccines and the risk of multiple sclerosis and other central nervous system demyelinating diseases. JAMA Neurol. 2014 Dec;71(12):1506-13. 97-Are 20 human papillomavirus types causing cervical cancer? J Pathol. 2014 Dec;234(4):431-5. 98-Relation of human papillomavirus status to cervical lesions and consequences for cervical-cancer screening: a prospective study. Lancet. 1999 Jul 3;354(9172):20-5.99-Natural history of cervical human papillomavirus infection in young women: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2001 Jun 9;357(9271):1831-6.

100-Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009 Jul 25;374(9686):301-14. 101-Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014 Feb 8;383(9916):524-32. 102-Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007 Jul;7(7):453-9. 103-Discrepant HPV/cytology cotesting results: Are there differences between cytology-negative versus HPV-negative cervical intraepithelial neoplasia? Cancer Cytopathol. 2017 Oct;125(10):795-805. 104-Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrenttesting for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Jul;12(7):663-72. 105-International standardization and classification of human papillomavirus types. Virology. 2015 Feb;476:341-344. 106-Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007 Aug 15;298(7):743-53. 107-Impact of an HPV6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine on progression to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in seropositive women with HPV16/18 infection. Int J Cancer. 2011 Dec 1;129(11):2632-42. 108-HPV Screening and Vaccination Strategies in an Unscreened Population: A Mathematical Modeling Study. Bull Math Biol. 2019 Nov;81(11):4313-4342. 109-Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018. 110-American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012 May-Jun;62(3):147-72. 111-Ten-year immune persistence and safety of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in females vaccinated at 15-55 years of age. Cancer Med. 2017 Nov;6(11):2723-2731. 112-Adapting cervical cancer screening for women vaccinated against human papillomavirus infections: The value of stratifying guidelines. Eur J Cancer. 2018 Mar;91:68-75. 113-A ten-year study of immunogenicity and safety of the AS04-HPV-16/18 vaccine in adolescent girls aged 10-14 years. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7-8):1970-1979. 114-Optimal Cervical Cancer Screening in Women Vaccinated Against Human Papillomavirus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016 Oct 18;109(2):djw216. 115-Effectiveness of cervical cancer screening over cervical cancer mortality among Japanese women. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006 Aug;36(8):511-8. 116-Cervical Cancer Screening Programs in Europe: The Transition Towards HPV Vaccination and Population-Based HPV Testing. Viruses. 2018 Dec 19;10(12):729. 117-Evaluation on the persistence of anti-HPV immune responses to the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in Chinese females and males: Up to 3.5 years of follow-up. Vaccine. 2018 Mar 7;36(11):1368-1374. 118-Detection of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus in Cervix Sample in an 11.3-year Follow-Up after Vaccination against HPV 16/18. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017 Aug;39(8):408-414. 119-Long-term immunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety of nine-valent human papillomavirus vaccine in girls and boys 9 to 15 years of age: Interim analysis after 8 years of follow-up. Papillomavirus Res. 2020 Jul 11;10:100203. 120-Impact of scaled up human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical screening and the potential for global elimination of cervical cancer in 181 countries, 2020-99: a modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Mar;20(3):394-407. 121-Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Feb;8(2):e191-e203. 122-Crystal structures of four types of human papillomavirus L1 capsid proteins: understanding the specificity of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2007 Oct 26;282(43):31803-11. 123-Naturally occurring capsid protein variants L1 of human papillomavirus genotype 16 in Morocco. Bioinformation. 2017 Aug 31;13(8):241-248. 124-Currently approved prophylactic HPV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009 Dec;8(12):1663-79. 125-Abundance of HPV L1 Intra-Genotype Variants With Capsid Epitopic Modifications Found Within Low- and High-Grade Pap Smears With Potential Implications for Vaccinology. Front Genet. 2019 May 24;10:489. 126-Whole-Genome Sequencing and Variant Analysis of Human Papillomavirus 16 Infections. J Virol. 2017 Sep 12;91(19):e00844-17. 127-Within-Host Variations of Human Papillomavirus Reveal APOBEC Signature Mutagenesis in the Viral Genome. J Virol. 2018 May 29;92(12):e00017-18. 128-Prevalence of human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: a worldwide perspective. International biological study on cervical cancer (IBSCC) Study Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995 Jun 7;87(11):796-802. 129-Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999 Sep;189(1):12-9. 130-HPV-negative carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a distinct type of cervical cancer with poor prognosis. BJOG. 2015 Jan;122(1):119-27. 131-Reframing cervical cancer prevention. Expanding the field towards prevention of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases. Vaccine. 2012 Nov 20;30 Suppl 5:F1-11. 132-Variations in the age-specific curves of human papillomavirus prevalence in women worldwide. Int J Cancer. 2006 Dec 1;119(11):2677-84. Polikistik Over

Polikistik Over